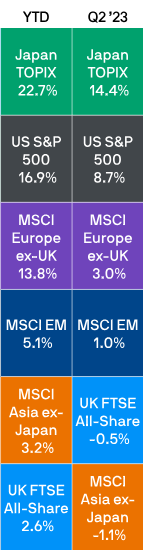

We thought it might be interesting to address three current topics: structural issues in the equity markets, housing and artificial intelligence. But first let us take a look at the performance of the main equity markets year to date:

The above table shows the YTD (to 30 June) and Q2 performances of some of the major market indices (source JP Morgan). It is very clear from this table that the UK is lagging and we would suggest that part of the reason for this lag is currency. Part is the lack of institutional interest. Part is political insecurity. Part is a sense that the Bank of England has lost the plot and that inflation is now set in for the duration – though even the inflation bears have not so far found a way consistently to beat it. Inflation bears were arguing that the commodities focus of the UK would be helpful but in fact this has not worked as a hedge (see also the performance of the Australian market).

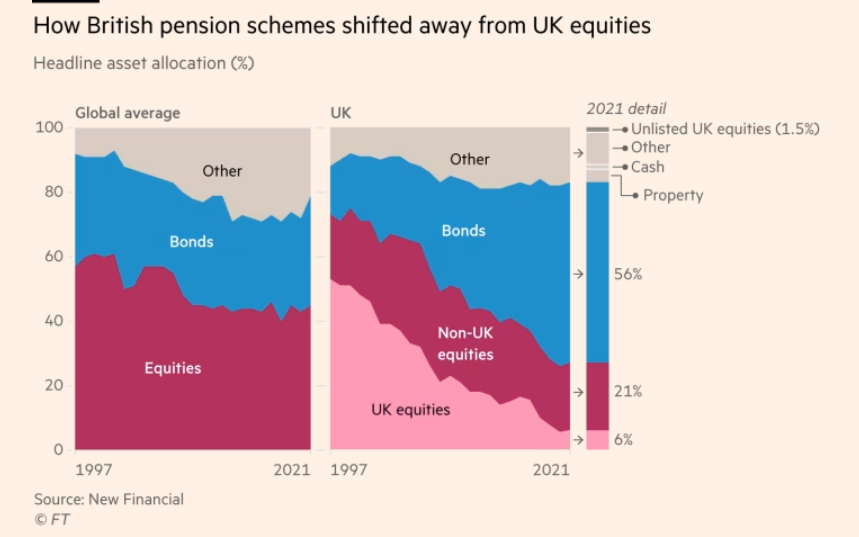

With regards to the lack of institutional interest – there are currently a plethora of studies on the UK listing regime and on other aspects of regulation, in an attempt to find a magic wand to wave to restore activity to the UK market. They largely miss the point. Listing in the US is harder and more expensive than here. The differentiating factor is the availability of large pools of capital. The UK has systematically discouraged pension funds from investing in private and illiquid assets, and in domestic equities. There were good reasons for the first (assorted pension fund scandals) and less good for the second (EU rules preventing the favouring of domestic investment). This has extended to private investment where tax breaks are extended to investment in overseas assets (ISAs – the old PEPs at one stage were UK-only). Indeed there is no shortage of EIS qualifying companies with a trivial presence in the UK. The net result was and continues to be to drive pension funds into investing in gilts however low the return. This is convenient for the Treasury but lamentable for the economy. The opposition’s one suggestion so far – pooled pension funds – has now been seized by the government, and in any event does not seem that significant. Until the problem is cracked, no amount of tinkering with listing rules, dual share classes etc. will make a difference. Kate Bingham’s recent Times article (paywall) nailed the problem in an article bemoaning lack of UK investment in her sector:

“Two decades ago more than 50 per cent of British pension assets were invested in UK-listed equities and yielded a return of 9 to 10 per cent per annum, according to the institute’s research. Now, that figure has fallen to just 4 per cent invested in UK-listed equities, with a far greater proportion invested in government bonds instead with average actual returns of 3 per cent over the last ten years. Last year the Bank of England even had to bail out pension funds that had heavily invested in gilts. A lose-lose-lose situation for pensioners, businesses and taxpayers”.

Here it is in graphical format:

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s Mansion House speech appears to have taken some of this on board, but his commitment to persuading pension fund managers to commit 5% of funds (which funds is unclear) to unlisted equities raises questions about quantum, timing and for investors in AIM, whether unlisted includes the AIM market. Technically it does – a quotation on AIM is not, under UK regulation, a listing – but whether that is what the Chancellor intended we do not yet know. Clearly it would be a welcome development for LGB investors if it did. Hopefully we shall see more detail over the summer, and none of this feels likely to be reversed by a future Labour administration. We do not think a new administration will be tempted to tinker with the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS), but the AIM business relief inheritance tax exemption.

Meanwhile in AIM we see a slow but steady disappearance of companies we have watched, whether to industry consolidation (Yourgene, ECSC), or the USA (Spectral MD) though not in any number to private equity. Companies are running increasingly tight ships, painfully aware of the difficulty of raising fresh equity, cutting costs and non-core R&D, and extending cash runways. Our own investors are showing an increasing interest in the Gilts, Sterling treasury bill market and high-grade corporate bond markets, taking advantage of the rate rises, the tax breaks on bonds trading at discounts, and trying to mitigate against the effect of inflation. After years in which these assets offered negligible yields, they are now a useful counterpart to the relatively short-dated debt accessible through LGB’s MTN programmes.

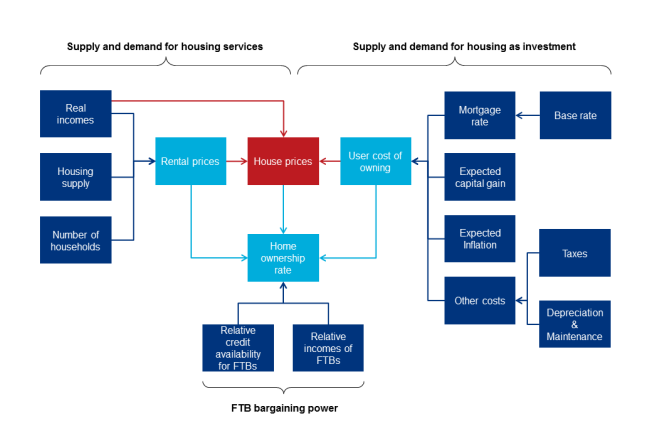

We have been taking a particular interest in the housing market having recently established an MTN programme for Roma Finance, a specialist property lender with an impressive track record and management team. The housing market is something on which everyone has an opinion, usually formed through the prism of their own situation, experience and aspirations. So for example journalists tend to be negative, often focussing on one metric (the house price to income relationship, usually) which reflects both the imperatives of writing a press article (keeping it simple) and perhaps also the long-term erosion in journalists’ pay over the last few decades (which may bring us on to AI – of which more below). It is intuitively obvious that house prices cannot be the outcome of a single variable. Indeed the price/income relationship was only a useful guide for a relatively short period starting some time after WW2. House prices are the outcome of – on the demand side income; the incidence of income tax; the increasing proportion of households with more than one earner; tax on property; land prices (itself driven by planning restrictions and property taxes); the tax treatment of interest payments; trends in household size; life expectancy; net emigration (up to the 1970s) or immigration; and on the supply side state intervention in housing provision (and destruction – the 1950s housebuilding boom was accompanied by mass slum clearance); the availability of capital and land for house builders. Other variables include changes in working patterns and regional shifts in employment (there is no shortage of affordable housing in East Lancashire or West Cumberland); and of course there are within this expectational effects and feedback loops.

There are of course a plethora of models. The OBR’s 2014 model which was informed by data back to the late 1960s and therefore included the sharp fall in prices in the early ‘90s and showed a reasonable fit for the period from 1980, presumably informed government policy to at least some extent. The Bank of England has generated various models, including this one, a model that shows “the rise in house prices relative to incomes between 1985 and 2018 can be more than accounted for by the substantial decline in the real risk‑free interest rate observed over the period….changes in the risk‑free real rate are a crucial driver of changes in house prices — the model predicts that a 1% sustained increase in index‑linked gilt yields could ultimately (i.e. in the long run) result in a fall in real house prices of just under 20%”. On which basis the swing in real yields evident in the Index Linked Market over the last 18 months will certainly doom the market. Perhaps we should be relieved the Bank’s forecasting record is so lamentable.

Oxford Economics published a useful paper in 2016 with a pleasingly sophisticated model looking not just at the usual inputs, but also disaggregating renting and owning, and focussing on the first time buyer (FTB) as the marginal player:

It also tried to allow for the feedback loops (using Structural Equation Modelling) between the direct and indirect effects of different factors. The conclusions for house prices were:

Interesting that upward pressure on rentals raises prices, whereas the increase in the mortgage rate has a rather subdued effect. But of course this is only one model.

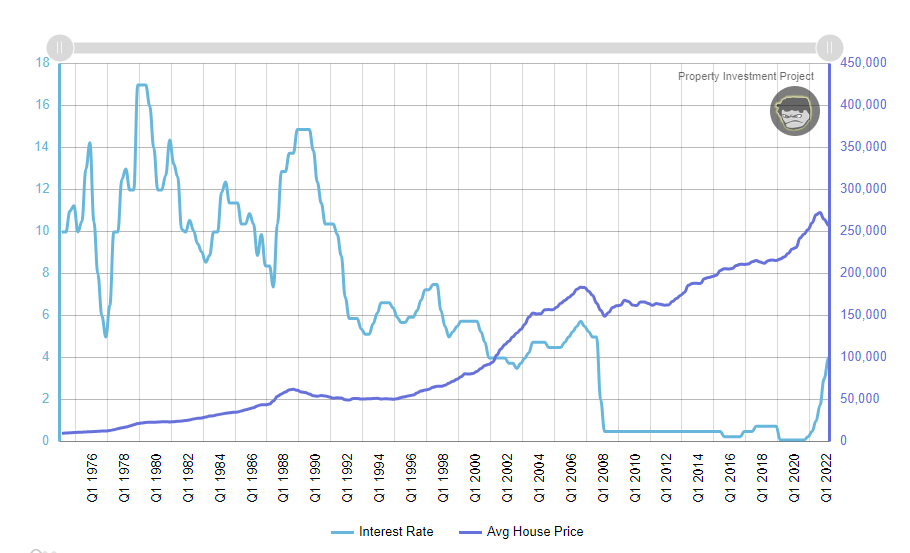

The point of this is not to try to find the best model, which would be a protracted exercise and one for which I have neither the time, energy or expertise, but to try to formulate a way to conceptualise what is going on. It is a City truism that “the trend is your friend”, as it is corollary..”till the end of the trend…”.Trends tend to continue till something important changes – waiting for mean reversion can be an awfully long wait, and whilst it is happening the mean converges on the trend rather than being a constant. However, something important has changed – the trajectory of interest rates. Is that enough to derail the housing market or is it different this time? Whilst I may not be an econometrician I am at least a sometime economic historian. Let’s look at the recent past (back to the mid ‘70s):

(I presume the scowling face in the top right hand corner is that of someone expecting to see a clear inverse relationship. And failing).

We have had two sharp falls in the housing market in recent times: the sharp 2007/8 fall in prices of roughly 25% triggered by the Global Financial Crisis, which was accompanied by a sharp fall in rates, and the similar percentage fall in the early ‘90s, (roughly from summer ’89 to early 1993) which was triggered by very high interest rates – as well as a recession. But looking back it certainly does not look as if interest rates are the sole or even a consistent driver.

Thinking about what is going on in the UK at the moment, we have continued upward pressure on household formation driven by strong net immigration (and bolt-hole purchasing, e.g. from Hong Kong), as well as the secular trends towards smaller households. We have a constipated planning system and no sign of a material increase in the supply of new housing (and no reason to think that an incoming Starmer administration could change this quickly). We have dislocation in the rental market which is driving rents up. Existing home owners will in some cases be forced to sell due to higher rates, but many are older, debt free, and benefitting from index-linked pensions and higher nominal returns on savings (incidentally the Bank of Mum and Dad will be doing as well as other banks in the current environment). High frictional costs of moving discourage downsizing. On the other hand interest rates are certainly hurting (particularly first time and recent buyers), and inflation is eroding real incomes. Plus expectations for capital gains must already have evaporated. The brakes are on but we are not yet in reverse gear. Anecdotally we are hearing that the London property market is quite active, a reflection of pent-up demand and potential buyers having savings, and managing to negotiate discounts. So an adjustment down but not a downtrend.

It is certainly possible to see how the housing market could be much more seriously dislocated. UK property tax is remarkably low by global standards, and houses are a non-portable target for Chancellors looking for new sources of income (though not to the extent of endangering banks’ balance sheets – and so far a major change in domestic property taxation seems to be more something for Labour think-tanks than mainstream policy). A recession affecting employment would feed through to real incomes, as does sustained inflation. The banks may have already started restricting credit. From a credit point of view a few years of inflation may be no bad thing: the real price of housing can fall with the nominal price not moving, but the debts are not inflation-linked and this does not trigger defaults. Dislocation can create opportunity: certainly the management of Roma see their borrowers as having many profitable opportunities – but at the same time are ensuring that their credit exposure is to the borrower’s assets in the round, not to single projects.

In conclusion – you pays your money and you takes your choice. It does not feel to me like we are on the edge of a precipice. But there is certainly some slippage. Hopefully these are not famous last words!

I had a go at getting Chat GPT and BARD, Google’s version, to write this report for me. I have to say I was pretty unimpressed. Maybe you would have thought otherwise. Indeed so far my limited dealings with AI engines have not impressed me that much, but it is clear that they are improving quickly, will get better and presumably produce less anodyne (and maybe more factual) responses. AI as trumpeted by companies claiming to use it is in many (most) cases really just machine learning – which is not particularly new. I asked ChatGPT to explain the difference and to be fair it did quite a good job (of regurgitating Wikipedia, I suspect…) – the concluding paragraph was “In summary, AI encompasses machine learning but goes beyond it by incorporating additional components such as reasoning, decision-making, knowledge representation, adaptability, and autonomy. AI systems aim to simulate human-like intelligence and perform complex tasks that require understanding, context, and a broader range of capabilities”.

We have had AI-related excitement before. There was a rash of AI-enabled drug discovery companies listed a couple of years ago. Here is one, the UK-based, Nasdaq-listed Exscientia. So far it would be fair to say it has not delivered.

Renalytix, a diagnostics company listed on AIM as Renalytix AI, dropped the AI when it re-listed on Nasdaq, the CEO conceding that really what they did was machine learning. The wheel has turned quickly – Spectral MD which is moving to Nasdaq in a SPAC deal is going to appear there as Spectral AI. Undoubtedly though the application of AI to diagnostics and to drug discovery will be transformative over time. And the effective use of machine learning in itself is not to be sniffed at.

So – what to do? There is clearly going to be a huge buzz around this and many companies will claim that they have the secret sauce. Applications as well as healthcare will include gaming, finance, robotics (autonomous vehicles that work?), entertainment and no doubt many more. Claims will run ahead of delivery in many cases. The theme is not correlated with the wider economy, and promoters will suggest it offers exponential returns.

One interesting angle is to consider who can supply something to feed these LLMs (Large Language Models) with something to differentiate the responses. The LLMs are trained by their owners (Microsoft, Google etc) on the internet as a whole as well as on their own data. They are therefore looking more or less at the same thing. Companies that own proprietary information in quantity may therefore be in a position to monetise it. Unsurprisingly, Bloomberg (which has quite a clunky interface, still recognisable from its early days) is already boasting of its capability (e..g “Using AI to sort through market-moving news”) with its BloombergGPT. Scientific and academic journals, which largely sit behind paywalls, may become more valuable and publishers such as RELX (the old Reed Elsevier) may benefit. Thomson Reuters like Bloomberg has a huge bank of data. And more specialist data curators (such as AIM-listed Global Data plc) may find new ways to monetise their products.

The LLMs demand bigger and faster chips, and this will create incremental demand for integrated circuit (IC) design houses – the one UK-listed company is Sondrel PLC. The challenge here is to bring AI out of the cloud and into users own devices or networks (so-called Edge computing), which could create huge incremental demand.

Thinking back to the TMT boom of the beginning of the century, there were many rash claims and many absurd valuations. A lot of money was made (early on) and lost (later). However, we can now look back at the graveyard of false hopes and of businesses that failed to transform, faced with the internet – anyone remember Yellow Pages? There were in the end more losers than winners, and the winners won very big indeed. Schumpeter’s theory of Creative Destruction is worth keeping in mind!

LGB & Co. Limited

Tintagel House, 92 Albert Embankment

London

SE1 7TY

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Relationship Manager

Ellana joined LGB in March 2024 as a Relationship Manager for our investing clients. Prior to LGB, Ellana worked at Bellecapital, handling client relationships and supporting the portfolio management team. Ellana graduated with a First-Class in Mathematics from Cardiff University and has a Level 4 Investment Advice Diploma.

Adviser

Simon became an Advisor to the Board of LGB & Co. with a focus on business strategy and initiatives in March 2024. Simon has extensive experience debt capital markets and wealth management. He previously ran the client and then the investment business of Heartwood and became Chief Executive in 2008. He led its well-regarded acquisition by Handelsbanken in 2013. Simon subsequently became NED and Chair of AIM-listed WH Ireland Group PLC. He was also asked to represent the wealth management sector on the FCA Smaller Business Practitioner Panel from 2013-2016.

Finance Manager

Following a degree reading Chemistry at The Queen’s College, Oxford, Antonia trained to become a chartered accountant at a London-based audit firm. She then moved into the tax sector joining EY and completing the chartered tax adviser qualification. She then gained further experience working as a finance director within industry at a family office / hedge fund.

Founder and Chairman

Andrew founded LGB & Co. in 2005 and is the Chairman of the company. He has a particular focus on the development of strategic relationships with corporate clients and business partners. Prior to founding LGB & Co., Andrew was a Managing Director at Citigroup Global Markets, where he was responsible for its fixed-income business with private banks and retail institutions. Earlier in his career Andrew worked at Schroders in London and Tokyo. Andrew graduated from Oxford University with a degree in Modern History. He is a chartered member of the Chartered Institute for Securities & Investment.

Capital Markets Director

Fergus advises corporate clients looking to raise debt and equity capital. He is also responsible for the execution and ongoing management of LGB’s MTN Programmes. Fergus joined LGB in 2019 having started his career at Lloyds Banking Group on the graduate training programme, before moving to the Leveraged Finance division, where he focused on transactions with mid-market corporates and PE firms. Fergus holds an MSc in Petroleum Geology from the University of Aberdeen.

Adviser

Lisa has worked with LGB since 2015 in supporting the on-going cultural and organisational development of the firm, providing advice on strategic people matters. Since 2006, Lisa has been running her own consultancy and executive coaching business, People Possibilities Ltd. Her work is focused on supporting clients at an organisational, team and individual level to enable high performance,improve leadership capability and effect cultural and behavioural change. Previously Lisa has held senior HR leadership positions with Schroders, ABN AMRO and HSBC. Lisa graduated from the University of Birmingham with an honours degree in International Relations & French. She is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) and a qualified Executive Coach.

Adviser

Charles has played an important role in developing LGB & Co.’s investment approach by encouraging a focus on investing in businesses with strong IP or know-how with recurring revenue business models that can prosper throughout economic cycles. Charles brings over 30 years’ experience of investing in privately-owned and publicly-listed small and mid-market companies. He is a director of Larpent Newton & Co. and Hygea VCT plc. Charles qualified as a Chartered Accountant at Peat Marwick, now part of KPMG.

Programme size: £25m

Establishment Date: XX 2017

Number of issues: 20

Sector: Financial services

Focus: Loans and leasing

Programme size: £20m

Establishment Date: December 2017

Number of issues: 12

Sector: Marine tracking

Focus: Maritime surveillance and management

Associate

Ben joined LGB in October 2022 as an associate after spending three years as a credit analyst at 9fin, where he produced research on corporates in the European & US High Yield and distressed debt markets.Ben holds an MSc in Investment Management from Bayes Business School (formerly Cass) and is a CFA charter holder.

CEO

Cedric was appointed CEO in July 2022 after a period of 18 months as a COO. Cedric spent 15 years working on the energy and commodities sales and trading desks for global banks (BNP Paribas, BAML and MUFG). He gained extensive international exposure, being based in London and Singapore and covering transactions in all geographic regions. Cedric graduated from Global Executive MBA at INSEAD in 2018 and started working in the capital markets space for growth-stage companies. He is also a director of LGB.

Relationship Manager

Megan joined LGB in January 2021 as a Relationship Manager. She is responsible for all day-to-day transactions with investment clients and oversees the LGB Investments Platform and Deal Hub. Prior to LGB, Megan worked at Puma Investments, a tax-efficient investment provider, in the sales and investor services team. Megan graduated from the University of Bath with a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology. Megan obtained the CISI Level 4 Diploma in Investment Advice in October 2021.

Investment Director

Ivan is LGB’s Investment Director: he is responsible for developing LGB’s investment proposition in the context of the broader market and economic developments. He regularly meets individual company management teams to seek out and monitor investment opportunities. Ivan has served as a senior adviser to the Equity Division of Société Générale, and was previously Managing Director in charge of equity sales for them in London. Earlier in his career, Ivan worked at Morgan Stanley, Lazards and Schroders. He has degrees in history from Cambridge University & London University, and an MBA from Cass Business School.

Managing Director

Simone is responsible for LGB & Co.’s business with investing clients, who include institutional investors, wealth managers and sophisticated private investors. Simone’s team provides access to a range of compelling investment opportunities with a particular emphasis on proprietary medium term note and equity transactions. Simone manages the portfolios of clients who have entered into advisory or discretionary investment agreements with LGB Investments, and advises the fund managers of the Guernsey-based LGB SME Fund. Prior to joining LGB & Co., Simone worked in the institutional fixed income department of Citigroup Global Markets. She began her career at Citigroup Private Bank in Geneva. Simone graduated from the University of Lausanne with a degree in HEC, Business Administration. She is a Chartered Member of the Chartered Institute for Securities & Investments.